Thursday, November 18, 2010

Cool Cup

The Ausction house Sotherby's will auction off a substantial private collection of African art in Paris on November 30th 2010, There is a lot to learn from this auction.

http://www.sothebys.com/liveauctions/A_New_York_Collection.pdf

This piece really intrigued me because of the two drinking receptacles on their underside, and the oddness of the hair and the squareness of the face compared to other Luba works. The squareness of the jaw reminds me more of the work of the Dagon people.

Magnificent Royal cup, Kalundwe peoples, western Luba, Democratic Republic of the Congo

(History: The Luba empire, which at one time stretched from the west all the way to Lake Tanganyika, was at its most powerful from around 1500 to the 1870's, when expansion reached east to lake's edge. The decline of Luba power began soon afterwards, and can be traced to Arab slave raiders and European colonialists, who did not recognize the power of Luba laws and rituals, and alas, also possessed rifles and horses. Though no longer politically powerful, Luba influences are still felt today throughout much of the DRC.)

Royal cups shaped like human heads with twin drinking receptacles on their underside are among the rarest of

Luba and Luba-related insignia. There are only a few such objects, and each is singular in its aesthetic elaboration.

Most cups of this type have emanated from Kanyok people and perhaps related groups to the west of the Luba heartland. This cup has been attributed to a workshop in the Kalundwe region (Felix 1987: 48-49; Neyt 1993: 212), not far from the Luba heartland, as evidenced by certain formal attributes. It also bears a close resemblance to a cup in the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde, (now called The Ethnological Museum) purchased by the museum from Hermann Haberer in 1925.

The Berlin and this cup are similar: Each possesses a dramatic coiffure with elegantly striated, voluptuous

chignons, cowry-shell shaped eyes, and the tongue slightly protruding from the mouth. This cup does not have the metal pins that adorn the Berlin cup, which are used to "fasten the spirit" (Roberts and Roberts 1996: 68; 2007: 32).

However, this example does have a hole carved into the top of the coiffure which may have been used for the

insertion of powerful medicinal substances to activate the sculpted head and to render it efficacious.

Luba cups of this sort were documented by the late Albert Maesen, former Head of the Ethnography Section at the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren, who conducted research and a collecting mission in southern Belgian Congo in the 1950s. Maesen reports that among the Kanyok, royal drinking vessels were the only objects he was not permitted to see in a storeroom in which the ruler's emblems were guarded, including thrones and scepters. He was allowed to view the rectangular box in which the cups were kept, but he was informed that they were only used during a ruler's investiture and for other sacred occasions (A. Maesen, personal communication, 1987).

Maesen found that royal cups called musenge were also used in a ceremony to honor paternal ancestral spirits, when a titleholder made an offering of cooked cassava (also called yuca or manioc- Kalundwe is mad up of the word manioc, lulundu, plus the diminitive ka; the Bena Kalundwe are the "people of Manioc") while the ruler communed with his ancestors. The chief counselor named Shinga Hemb drank palm wine from one side of the cup and then passed it to the participants who drank from the other side. Similar acts were performed after divination or at the rising of a new moon (A. Maesen, personal communication, 1982).

The secrecy associated with these royal cups and their limited number suggests another possible association: Early colonial sources and oral traditions point to the importance of the skull of the previous ruler to the investiture of his successor. The skull was the vehicle through which the new ruler obtained power, blessing, and wisdom from his predecessor and validated his own link in the chain of political and moral authority. Quiet contemplation with the skull was essential to investiture, and some writers assert that the king consumed human blood from the cranium, to effect his transformation from an ordinary human being to a semi-divine ruler (Verbeke 1937: 59; Van Avermaet and Mbuya 1954: 709-711; Theuws 1962:216). Indeed, the Luba word for royalty, bulopwe," refers to "the status of the blood" (Roberts and Roberts 2007:32). It has been asserted that carved wooden cups might have replaced and symbolized the use of skulls in important rituals (Huguette Van Geluwe, personal communication, 1982). Such an assertion remains a hypothetical explanation for the existence of these beautifully carved and carefully concealed cups.

The gender of this strikingly sculpted head cannot be ascertained with certainty. Its elaborate coiffure would

suggest a female hairdo judging from other Luba emblems, yet chiefs and kings were known to don women's

coiffures during their investitures, thus reinforcing the complexities that Luba ascribe to political authority. In many contexts of Luba and Luba-related culture, women serve as guardians of royal secrets and possess other remarkable prerogatives and powers. They have long held roles as diplomats, ambassadors, advisors, and counselors to their male counterparts, and are responsible for the spiritual underpinnings of power itself. Only a woman's body is considered to be strong enough to hold the spirit of a king, and a king was often referred to as a woman by Luba officials. Such deliberately ambiguous gendering of power allows the special attributes of men and women to coalesce in bulopwe, the realm of royalty that is not qualified by gender, as the word "kingship" is in English-speaking contexts.

This particular royal cup has another trait that associates it with womanhood: its visibly protruding tongue. A Luba woman named Ngoi Zaina explained that this artistic motif was the sign of a woman ready for courtship, marriage, and childbearing, and therefore suggested that a woman was in the prime of her life (Nooter 1991: 250). Luba sculptures usually represent female figures with attributes of Luba beauty, including dense scarification marks and elegant coiffures. A spirit is attracted to an emblem of royal power that bears these marks of beauty, just as men are to those of a woman. In effect, a Luba cup such as this one must have been a magnet for spiritual power, a receptacle of royal secrets, and a symbol of continuity for the dynastic line.

Mary Nooter Roberts, UCLA

Labels:

African art,

drinking receptacle,

functional art,

Luba

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

Rarely seen Leonard Tsuguoharu Foujita sells at Sotherbys

One of the lesser know Modernist Leonard Tsuguoharu Foujita painting JEUNE FILLE À LA CORBEILLE DE FRUITS sold at Sotherby's Impressionist and Modern Day Art Sale in New York

on Wed, 03 Nov 10, for $350,000 USD. The piece came from a private collection.

There is a lot to like about this picture by Foujita- the smart foreshortening of the figure and the bench; the subtle coloring being most dramatic with the fuit; the position of the hand holding the peach?; the oversized head; the direct look; the imperfect mouth; the oddness of the background behind the sitter being in a sense framed by wood.

About Foujita

Leonard Tsuguoharu Foujita (November 27, 1886 – January 29, 1968) was a painter and printmaker born in Tokyo, Japan who applied Japanese ink techniques to Western style paintings.

In 1910 when he was twenty-four years old Foujita graduated from what is now the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Three years later he went to Montparnasse in Paris, France. When he arrived there, knowing nobody, he met Amedeo Modigliani, Pascin, Chaim Soutine, and Fernand Léger and became friends with Juan Gris, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Foujita claimed in his memoir that he met Picasso less than a week after his arrival, but a recent biographer, relying on letters Foujita sent to his first wife in Japan, clearly shows that it was several months until he met Picasso. He also took dance lessons from the legendary Isadora Duncan [1].

Foujita had his first studio at no. 5 rue Delambre in Montparnasse where he became the envy of everyone when he eventually made enough money to install a bathtub with hot running water. Many models came over to Foujita's place to enjoy this luxury, among them Man Ray's very liberated lover, Kiki, who boldly posed for Foujita in the nude in the outdoor courtyard. Another portrait of Kiki titled "Reclining Nude with Toile de Jouy," shows her lying naked against an ivory-white background. It was the sensation of Paris at the Salon d'Automne in 1922, selling for more than 8,000 francs.

His life in Montparnasse is documented in several of his works, including the etching A la Rotonde or Café de la Rotonde of 1925/7, part of the Tableaux de Paris series published in 1929.[2] {From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsuguharu_Foujita}

posted by Paul Grant (follower of Basho)

on Wed, 03 Nov 10, for $350,000 USD. The piece came from a private collection.

There is a lot to like about this picture by Foujita- the smart foreshortening of the figure and the bench; the subtle coloring being most dramatic with the fuit; the position of the hand holding the peach?; the oversized head; the direct look; the imperfect mouth; the oddness of the background behind the sitter being in a sense framed by wood.

About Foujita

Leonard Tsuguoharu Foujita (November 27, 1886 – January 29, 1968) was a painter and printmaker born in Tokyo, Japan who applied Japanese ink techniques to Western style paintings.

In 1910 when he was twenty-four years old Foujita graduated from what is now the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Three years later he went to Montparnasse in Paris, France. When he arrived there, knowing nobody, he met Amedeo Modigliani, Pascin, Chaim Soutine, and Fernand Léger and became friends with Juan Gris, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Foujita claimed in his memoir that he met Picasso less than a week after his arrival, but a recent biographer, relying on letters Foujita sent to his first wife in Japan, clearly shows that it was several months until he met Picasso. He also took dance lessons from the legendary Isadora Duncan [1].

Foujita had his first studio at no. 5 rue Delambre in Montparnasse where he became the envy of everyone when he eventually made enough money to install a bathtub with hot running water. Many models came over to Foujita's place to enjoy this luxury, among them Man Ray's very liberated lover, Kiki, who boldly posed for Foujita in the nude in the outdoor courtyard. Another portrait of Kiki titled "Reclining Nude with Toile de Jouy," shows her lying naked against an ivory-white background. It was the sensation of Paris at the Salon d'Automne in 1922, selling for more than 8,000 francs.

His life in Montparnasse is documented in several of his works, including the etching A la Rotonde or Café de la Rotonde of 1925/7, part of the Tableaux de Paris series published in 1929.[2] {From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsuguharu_Foujita}

posted by Paul Grant (follower of Basho)

Friday, May 1, 2009

The power of a picture- Photogropher Platon

The New Yorker and photographer Platon won a National Magazine Award for a series of portraits of American war veterans and their loved ones. This summer, the photographer Platon took pictures of hundreds of men and women who volunteered to serve in the military and were sent to Iraq or Afghanistan. He followed them on their journey through training and deployment, after demobilization and in hospitals, to compile a portrait of the dedication of the armed services today.

Colin Powell Cites Platon Photo In Obama Endorsement

President Bush's former Secretary of State Colin Powell was moved to endorse Barack Obama in part by a photo he saw in a magazine. On Meet The Press this morning, Powell said he was troubled by members of the Republican party falsely suggesting that Obama is a Muslim and therefore associated with terrorists:

"I feel strongly about this particular point because of a picture I saw in a magazine. It was a photo essay about troops who were serving in Iraq and Afganistan. And one picture at the tail end of this photo essay was a mother in Arlington Cemetry, and she had her head on the headstone of her son's grave. And as the picture focused in, you could see the writing on the headstone. And it gave his awards, Purple Heart, Bronze Star, showed that he died in Iraq, gave his date of birth, date of death. He was 20 years old. And then at the very top of the headstone, it didn't have a Christian Cross. It didn't have a Star of David. It had a crescent and a star of the Islamic faith. And his name was Kareem Rashad Sultan Khan. And he was an American."

Platon

Born in London in 1968, Platon was raised in the Greek Isles by his English mother, an art historian, and Greek father, an architect, until the age of seven when his family returned to London. He attended St. Martin's School of Art, and after receiving his BA with honors in Graphic Design, he was then awarded an MA in photography and fine art at the Royal College of Art, where one of his professors and mentors was the late John Hind, the creative director of British Vogue. While still a student, he received British Vogue's "Best up-and-coming Photographer" award in 1992, along with the opportunity to contribute both fashion and portrait images to the magazine.

Now an Englishman in New York, Platon left London in 1998 after spending a few years working for George, the magazine about politics and media culture founded by the late John F. Kennedy, Jr. Recruited to shoot for its premiere issue, Platon maintained a long-term relationship with the magazine and Kennedy, and this significant and incomparable introduction to American culture and politics included one of Platon's favorite assignments: a cross-country trip in order to document the 20 most fascinating men in America.

Since the early 1990s, Platon has continued to shoot portrait, fashion and documentary work for a range of international publications, including The New Yorker, Time Magazine, Rolling Stone, The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, Harpers Bazaar, Esquire, GQ, Newsweek, Arena, The Face, i-D, The Sunday Telegraph, The Observer, and The Sunday Times. His advertising credits include campaigns for the Wall Street Journal, Motorola, Nike, Converse, Verizon, Vittel, Levi's, IBM, Rolex, Ray-Ban, Tanqueray, Kenneth Cole, Issey Miyake, Moschino, Timex and Bertelsmann among others.

In 2007 Platon photographed Russian Premier Vladimir Putin for Time Magazine's Person Of The Year Cover. This image was awarded the coveted 1 st prize at 2008 World Press Photo Contest.

Platon is now a staff photographer at The New Yorker, signing a multi-year contract in 2008.

Platon's first monograph "Platon's Republic", was published in 2004 by Phaidon Press. To coincide with its publication, he had solo portrait exhibitions at the Milk Gallery in New York and the Ex-Saatchi gallery in London. The same year, his first solo show of documentary work from around the world was held at the Leica Gallery in New York. His work also has been exhibited at Hamilton's Gallery in London, Spiral Hall in Tokyo, Carla Sozzani Gallery in Milan and Galerie Thierry Marlat in Paris.

Platon is represented worldwide by David Maloney, at Art Department in New York. He can be reached at (212) 925-4222 X108 or davidm@art-dept.com

Platon is based in New York where he lives with his wife, daughter and son.

Colin Powell Cites Platon Photo In Obama Endorsement

President Bush's former Secretary of State Colin Powell was moved to endorse Barack Obama in part by a photo he saw in a magazine. On Meet The Press this morning, Powell said he was troubled by members of the Republican party falsely suggesting that Obama is a Muslim and therefore associated with terrorists:

"I feel strongly about this particular point because of a picture I saw in a magazine. It was a photo essay about troops who were serving in Iraq and Afganistan. And one picture at the tail end of this photo essay was a mother in Arlington Cemetry, and she had her head on the headstone of her son's grave. And as the picture focused in, you could see the writing on the headstone. And it gave his awards, Purple Heart, Bronze Star, showed that he died in Iraq, gave his date of birth, date of death. He was 20 years old. And then at the very top of the headstone, it didn't have a Christian Cross. It didn't have a Star of David. It had a crescent and a star of the Islamic faith. And his name was Kareem Rashad Sultan Khan. And he was an American."

Platon

Born in London in 1968, Platon was raised in the Greek Isles by his English mother, an art historian, and Greek father, an architect, until the age of seven when his family returned to London. He attended St. Martin's School of Art, and after receiving his BA with honors in Graphic Design, he was then awarded an MA in photography and fine art at the Royal College of Art, where one of his professors and mentors was the late John Hind, the creative director of British Vogue. While still a student, he received British Vogue's "Best up-and-coming Photographer" award in 1992, along with the opportunity to contribute both fashion and portrait images to the magazine.

Now an Englishman in New York, Platon left London in 1998 after spending a few years working for George, the magazine about politics and media culture founded by the late John F. Kennedy, Jr. Recruited to shoot for its premiere issue, Platon maintained a long-term relationship with the magazine and Kennedy, and this significant and incomparable introduction to American culture and politics included one of Platon's favorite assignments: a cross-country trip in order to document the 20 most fascinating men in America.

Since the early 1990s, Platon has continued to shoot portrait, fashion and documentary work for a range of international publications, including The New Yorker, Time Magazine, Rolling Stone, The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, Harpers Bazaar, Esquire, GQ, Newsweek, Arena, The Face, i-D, The Sunday Telegraph, The Observer, and The Sunday Times. His advertising credits include campaigns for the Wall Street Journal, Motorola, Nike, Converse, Verizon, Vittel, Levi's, IBM, Rolex, Ray-Ban, Tanqueray, Kenneth Cole, Issey Miyake, Moschino, Timex and Bertelsmann among others.

In 2007 Platon photographed Russian Premier Vladimir Putin for Time Magazine's Person Of The Year Cover. This image was awarded the coveted 1 st prize at 2008 World Press Photo Contest.

Platon is now a staff photographer at The New Yorker, signing a multi-year contract in 2008.

Platon's first monograph "Platon's Republic", was published in 2004 by Phaidon Press. To coincide with its publication, he had solo portrait exhibitions at the Milk Gallery in New York and the Ex-Saatchi gallery in London. The same year, his first solo show of documentary work from around the world was held at the Leica Gallery in New York. His work also has been exhibited at Hamilton's Gallery in London, Spiral Hall in Tokyo, Carla Sozzani Gallery in Milan and Galerie Thierry Marlat in Paris.

Platon is represented worldwide by David Maloney, at Art Department in New York. He can be reached at (212) 925-4222 X108 or davidm@art-dept.com

Platon is based in New York where he lives with his wife, daughter and son.

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Picasso's Bull Lithograph of 1945

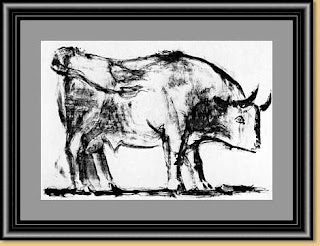

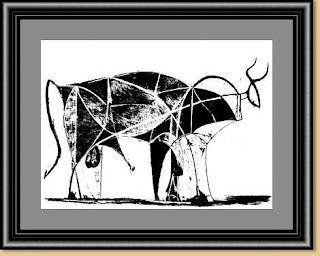

Bull ( Plate I. - December 5 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Pablo Picasso created 'Bull' around the Christmas of 1945. 'Bull' is a suite of eleven lithographs that have become a master class in how to develop an artwork from the academic to the abstract. In this series of images, all pulled from a single stone, Picasso visually dissects the image of a bull to discover its essential presence through a progressive analysis of its form. Each plate is a successive stage in an investigation to find the absolute 'spirit' of the beast.

To start the series, Picasso creates a lively and realistic brush drawing of the bull in lithographic ink. It is a fresh and spontaneous image that lays the foundations for the developments to come.

Picasso used the bull as a metaphor throughout his artwork but he refused to be pinned down as to its meaning. Depending on its context, it has been interpreted in various ways: as a representation of the Spanish people; as a comment on fascism and brutality; as a symbol of virility; or as a reflection of Picasso's self image.

Bull ( Plate II. - December 12 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

At the second stage of the lithograph, Picasso bulks up the form of the bull to increase its expressive power and achieve a more mythical presence.

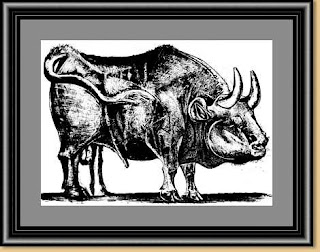

Bull ( Plate III. - December 18 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

On Plate III. the development takes a change of direction. Picasso stops building the beast and starts to dissect the creature with lines of force that follow the contours of its muscles and skeleton. He cuts into the form of the bull much in the same way as a butcher would cut up a carcass. In fact, he was known to have joked with the printers about this butcher analogy. Also at this stage, Picasso introduces the use of a lithographic crayon to add more detail to the surface texture of the animal's skin. The overall effect is reminiscent of Dürer's famous images of a rhinoceros.

Bull ( plate IV. - December 22 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

Plate IV. sees the artist start to abstract the structure of the bull by simplifying and outlining the major planes of its anatomy.

Ten years earlier Picasso had said that "A picture used to be a sum of additions. In my case a picture is a sum of destructions." In view of this statement, lithography seems to be the most natural choice of media for this series of prints. One of the technical advantages of lithography over other printmaking techniques is that you can both add to and subtract from the image with relative ease.

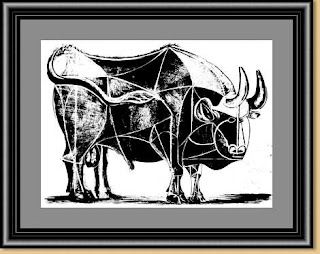

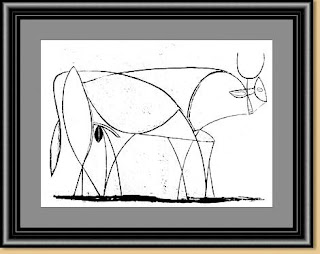

Bull ( plate V. - December 24 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

The simplification and stylisation of the image continues on Plate V. Picasso starts to erase sections of the bull in order to redistribute the balance and reorganise the dynamics between the front and the rear of the creature.

First, he reduces its massive head and compresses its features into the small area that was previously the bull's forehead. By enlarging the eye and flattening its horns into a more lyrical design, he creates a sharper focal point at the front of the animal.

Next, he erases a section of the back which has the counter effect of raising the front. He literally underlines this change with the bold white line that runs diagonally across the animal, parallel to the new angle of the back. As a counterbalance to this movement, he strengthens a line that runs in the opposite direction across the middle of the body, parallel to the shoulders at the front.

Picasso's process of development is like building a house of cards where balance and counterbalance of the individual elements is crucial to the stability of the whole.

Bull ( plate VI. - December 26 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

At this stage, another new head and tail are created to conform to the style and direction of the developing image.

Picasso introduces more curves to soften the network of lines that crisscross the creature. Once again he adjusts the line of the back which now begins as wave on the shoulders and flows like a pulse of energy along the length of its body. The two counterbalancing lines discussed in the previous plate are extended down the front and back legs to act like structural supports for the weight of the bull. All three of these lines intersect at a point that suggests the bull's center of balance. Through the development of these drawings, Picasso is beginning to understand the displacement of weight and balance between the front and rear of the animal.

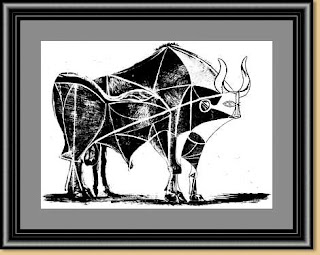

Bull ( plate VII. - December 28 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

As Picasso recognizes the balance of form in the bull, he starts to remove and simplify some of the lines of construction that have served their function. He then encases the essential elements that remain in a taut outline.

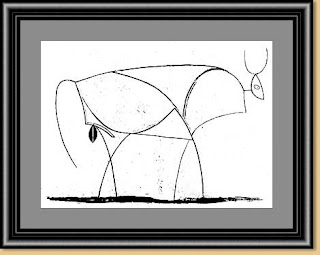

Bull ( plate VIII. - January 2 1946 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

Plate VIII. continues the reduction and simplification of the image into line with another reconfiguration of the head, legs and tail.

Bull ( plate IX. - January 5 1946 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

While continuing to have fun with the drawing of the head, Picasso now erases the remaining areas of tone and finally reduces the bull to a line drawing. Only the creature's reproductive organ retains its shading in order to emphasise its gender.

Bull ( plate X. - January 10 1946 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

At this penultimate stage, the more complex areas of the line drawing are removed to leave only a few basic lines and shapes that characterize the fundamental forces and correlation of forms in the creature.

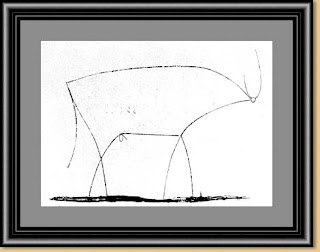

Bull ( plate XI. - January 17 1946 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

In the final print of the series, Picasso reduces the bull to a simple outline that is so carefully considered through the progressive development of each image, that it captures the absolute essence of the creature in as concise an image as possible.

Labels:

1945,

Picasso,

Picasso's bull,

Picasso's bull lithograph

A fresh look at a Cubist picture by Picasso

THE WASHINGTON POST

Published: April 5, 2009

WASHINGTON

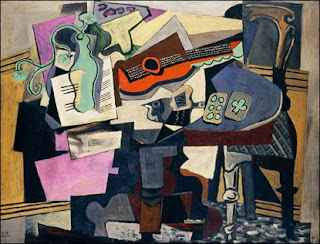

To watch a great art thinker's mind at work, we asked T.J. Clark to have a go at a Picasso that he hadn't known before, an untitled still life from 1918. It hangs in the East Building of the National Gallery.

The black

Clark had never really thought about Picasso's still life until we put him face to face with it. In reproductions that he's glimpsed, he's found the whole thing "terribly jolly." Not praise, coming from Clark. Standing in front of it, he's immediately struck by the "extraordinary black border" that wraps around three sides. That makes the whole scene graver, he says, noting how Picasso's black border creates a special tension between the "lighthearted bric-a-brac" that fills the painting's table and a sense of "grim confinement."

Coming very close to the painting, Clark points out how the dark paint actually covers areas in its bottom half that were once the same lively turquoise found on the painting's vase and cards. (The earlier paint peeks through cracks in the darker tones laid overtop.) Picasso, standing before his half-finished picture, seems to have had the same concerns about its "jolliness" as Clark.

Once Picasso had revised and completed the picture, Clark notes, he laid down a blood-red signature that crosses over between dark border and bright scene, laying claim to both.

The space

Clark is interested in the confined spaces and interiors you get in Picasso. Even when a picture's so kaleidoscopic that you can't make out the objects in it, he says, Picasso almost always gives a sense of the domestic space they're in. And, of course, you get just such a space in this picture's view into the corner of a room. Picasso, the great hater of abstraction, was always committed to delivering "something solid and felt," Clark said.

Stepping far back from the picture, Clark shows how well Picasso has achieved his end. What had looked like cubist complexities from up close resolve into a clear sense of a cluttered table standing in a corner with a chair. However close a Picasso painting comes to abstract pattern, Clark said, it has to "relate to some particular situation" in the real world.

Rather than dwelling on making each object separately clear and visible, that is, Picasso "wants to show us the way things in a certain world fit together." Picasso asks himself: "How imperiously can I play with these particular identities and still have them contribute to an overall interior?"

The past

For all its radically modern look, Clark said, the enclosed world seen in Picasso's pictures is essentially nostalgic. They depict the cozy world of a 19th-century bourgeois. For Picasso, Clark says, the bourgeoisie is a social force that is "both confining and wonderful." His interiors register that confinement, but they also revel in the comforts and objects that they gather into "the familiar space of the room."

Picasso had painted such old-fashioned rooms even when he was living in the mess of his unheated studio at the Bateau Lavoir. By 1918, when he's actually achieved the comforts of the bourgeoisie, he seems to step back from them -- to frame them in black and hold them up to sight.

The objects

Picasso depicts the "stock properties" of bohemian sociability -- guitar, sheet music, cards, fruit bowl, even maybe an absinthe spoon and glass at the front edge of the table. They are, Clark said, "utterly banal and familiar things -- they stand for the sufficiency of the bohemian world."

That world is "a mixture of the celebratory and the down-at-heels," Clark said. "Never was a carpet less luxurious -- or the stuffing in a chair." Although, in a typically Picassoid oxymoron, that down-at-heels carpet is also the one place in the painting where the artist resorts to showy brushwork.

By 1918, however, this very successful painter barely had a foot left in bohemia. His still life is looking back at something the artist has lost. The longer we look at the painting, Clark says, the more clearly it seems to be about "its stock properties being stock." Its vase and playing cards are cartoons of themselves, the fruits in its fruit bowl become four black-edged blobs of pink. "Never has fruit been more vestigial."

The moment

It, 1918, wasn't a good year for Europe, exhausted by a four-year war. If the painting wears black, that could be why.

Yet Clark insists that the picture is not portentous or histrionically doom-laden. Clark could imagine someone asking, "How dare a painter paint cards and a guitar in 1918 -- how can this painting be other than trivial?" And that's the question Picasso answers, in a painting of "tremendous gravity." Picasso, Clark said, wants us to "enter its world of familiar delights, but full of a sense of that world being something to struggle for."

The artist

The great achievements of cubism were over when this still life was painted, and there was a real risk that the movement was becoming empty style. "He knows that the moves are becoming too pre-established," Clark said. This last moment of cubism has the "terminal flavor" of "a language tremendously conscious of itself as a language, on the verge of just sedimenting up." The airless, lightless scene in this 1918 still life, Clark said, "is on the verge of not being vivid."

Clark wonders if Picasso uses the black border on this picture to show that he's aware of this. His border presents the scene as a work of art, as a framed picture, rather than as an unmediated view into a real portion of real space. That is, the painter is letting us know that he knows that his moves are starting to be more about painting than about the vivid world that they once showed.

Whereas earlier, fully cubist pictures, which tended to trail off into open blankness at their sides, had simply let us sense their space, without all the editorializing.

In this still life, then, Picasso's sense of space has started to register as a particular sense of confinement -- the confinement of a painter who feels trapped in an artistic style, too far from reality and truth.

Labels:

1918,

cubism,

National Gallery,

Picasso,

Picassoid oxymoron,

T.J. Clark

Friday, March 13, 2009

Video Portrait Comparison - Male vs Female

A nice video showing a comparison of drawing the face of a amle and female side by side

Tuesday, March 3, 2009

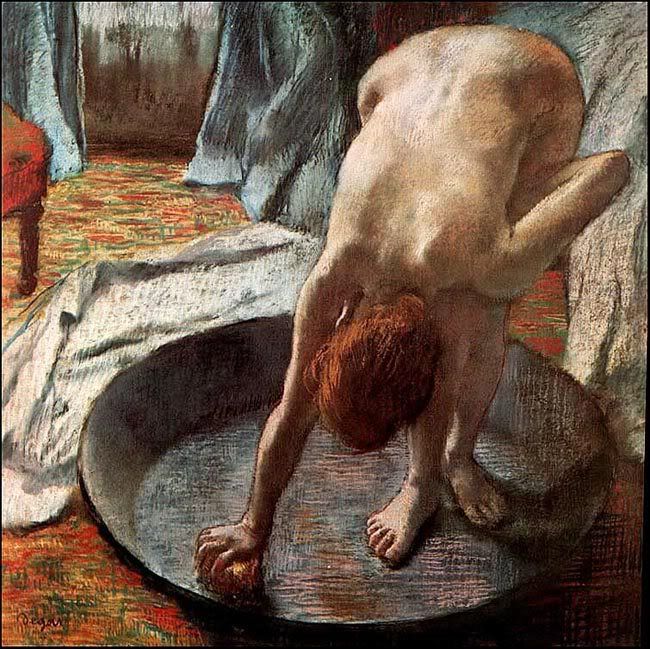

Artisitic potrayals of Woman Bathing in arts

Degas drew a great deal of criticism for his late pastel nudes. Women were rarely ever seen in the intimate act of bathing or dressing... even by their husbands... at least not women of higher social status. As such, it was immediately assumed that all of Degas' women were prostitutes. The use of expressive colors and textures..unexpected points of view...and odd croppings (influenced by photography)...made his work even more shocking to the audience of his time.

Two Young Women Bathing in the Woods

1929

Roland Oudot, French, 1897–1981

"Women bathing." Paul Cézanne did many pictures of nude women bathing during his career and the Ordrupgaard collection has a good example that the catalogue notes was "made in the context of other pictures, photographs, and reproductions of nude figures form the Musée du Louvre and in Cézanne's early drawings and sketches of work by Delacroix, Michelangelo, Puget and Rubens." "This frieze-like composition - vivid as it is in painterly terms - is just as artificial, construced, and conceptual as his strange early figure paintings. ...In Cézanne's work the spiritual, in the Symbolist sense, has no place, just as his Utopian vision includes neither concrete nor imagined physical reality. His bathers are a far cry from the nymphs and carefree nude figures found in the pictures of Auguste Renoir and Henri Matisse. Cézanne's bathers are physically present but paradocially dispasionate and inactive. It is a concept of joie de vivre that lacks both joie and vivre."

Art Deco is an elegant style of decorative art, design and architecture which began as a Modernist reaction against the Art Nouveau style. It is characterized by the use of angular, symmetrical geometric forms. One of the classic Art Deco themes is that of 1930s-era skyscrapers such as New York's Chrysler Building and Empire State Building. The former, designed by architect William Van Alen, is considered to be one of the world's great Art Deco style buildings.

The Art Deco look is related to the Precisionist art movement, which developed at about the same time.

Well-known artists within the Art Deco movement included Tamara de Lempicka,

'A Woman bathing in a Stream (Hendrickje Stoffels?)'

1654

REMBRANDT

1606 - 1669

NG54. Holwell Carr Bequest, 1831.

Signed and dated bottom right: Rembrandt f 1654

The model is probably Hendrickje Stoffels (about 1625/6 - 1663). She lived in Rembrandt's household from about 1649 until her death. She became his common-law wife and bore him a daughter, Cornelia, who was baptised on 30 October 1654 (the year of this painting). It has been suggested that the sumptuous red robe on the river bank indicates that the painting might be a sketch for a religious or mythological picture; the model might be in the guise of an Old Testament heroine, such as Susanna or Bathsheba, or the goddess Diana, who were all spied upon by men while bathing. However, there is no evidence for a completed painting after this work and, moreover, Rembrandt did not use oil sketches as preparation for larger-scale paintings.

The handling of the paint is unusually spontaneous. The picture appears unfinished in some parts, for example, in the shadow at the hem of the raised chemise, the right arm and the left shoulder, but it was clearly finished to Rembrandt's satisfaction since he signed and dated it.

Oil on oak

61.8 x 47 cm.

Oil on Canvas, Paul Gauguin, Tahitian Women Bathing

Oil on Canvas, Paul Gauguin, Tahitian Women BathingCompleted in 1892

Mary Cassatt - Woman Bathing - Colored Drypoint and Aquatint - 1891

Print from Woman Artist Mary Cassatt

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)