by Elizabeth Roth

“Not only does the mind create art, it also perceives it,” began Randy Blakely, Ph.D., Allan D. Bass Chair in Pharmacology, and director, Center for Molecular Neuroscience, in his introduction of Dr. Christopher Tyler. Tyler, of the Smith Kettlewell Eye Institute, delivered the second lecture in the 2002 Brain Awareness program recently at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts.

Tyler discussed how the brain perceives symmetry and how artists, consciously or unconsciously, create their art based on an understanding of symmetrical principles.

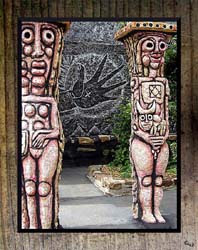

Symmetry is a key visual property for humans. Its importance is expressed in its ubiquitous use as a design principle in everything humans construct, from architecture to the pattern in Oriental rugs.

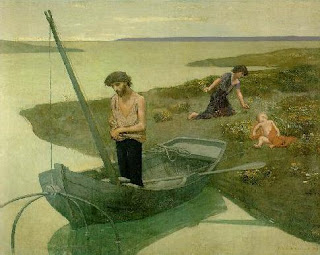

Defined as balanced form, a beauty of form arising from balanced proportions, it is no surprise, then, that elements of symmetry are apparent in works of art. But, it is only partial symmetry that we see. In many of the Renaissance works Tyler presented, architectural elements of a painting were symmetrical while figures in the foreground were arrayed. Similar examples from other eras and artistic styles were presented as well.

Perhaps, it was theorized, that artists were unconsciously using symmetry to represent order, harmony, or serenity while the asymmetrical elements depicted that life and art are not perfect and therefore, cannot be perfectly symmetrical.

8

Perception, symmetry of art discussed at brain lecture

Through functional magnetic resonance imaging, it is clear that the brain reacts to symmetry in the occipital lobe, the primary part of the brain that reacts to visual stimuli. Tyler’s research indicates that human symmetry processing is hard-wired. In a matter of less than .05 of a second, humans instinctively scan a visual object for symmetrical qualities.

Questions were raised during the lecture about an evolutionary bias toward symmetry, possibly due to the fact that symmetrical bodies, biologically speaking, seem to be the best designed for procreation. Studies have shown that those human faces that are widely considered to be the most attractive are also quite symmetrical. Is this equivocation of symmetry to beauty, as was asked during the lecture, why humans very often tilt their head to one side as they speak directly to someone, or they stand with one foot forward, at an angle, perhaps in an attempt to mask any asymmetry? Could this explain the subconscious attention to symmetry in so many works of art?? Could this explain the subconscious attention to symmetry in so many works of art?

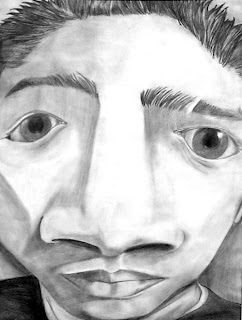

Symmetrical elements are often found in artistic works, and specifically paintings throughout many eras. Tyler noted that one of the clues to the importance of symmetry is evident in the placement of eyes in painted portraits.

According to Tyler, a survey of portraits over the last two millennia revealed that throughout history, one eye tended to be placed symmetrically at or near the vertical axis of the canvas. This placement violates the inherent symmetry of the face and body, but expresses a deeper symmetry and concentration on the “window on the soul.” Perhaps the artists felt it was more accurate to represent their subjects in their realistic imperfection.

Interestingly, Tyler found this theme to be present in diverse works from various cultures. Despite Tyler’s extensive research, he indicated that he was unable to find any reference to this principle, leaving him to conclude that the artists were not purposefully centering eyes in their portraits, but rather, did so unconsciously.

From Publishers Weekly

Anyone who thinks math is dull will be delightfully surprised by this history of the concept of symmetry. Stewart, a professor of mathematics at the University of Warwick (Does God Play Dice?), presents a time line of discovery that begins in ancient Babylon and travels forward to today's cutting-edge theoretical physics. He defines basic symmetry as a transformation, "a way to move an object" that leaves the object essentially unchanged in appearance. And while the math behind symmetry is important, the heart of this history lies in its characters, from a hypothetical Babylonian scribe with a serious case of math anxiety, through Évariste Galois (inventor of "group theory"), killed at 21 in a duel, and William Hamilton, whose eureka moment came in "a flash of intuition that caused him to vandalize a bridge," to Albert Einstein and the quantum physicists who used group theory and symmetry to describe the universe. Stewart does use equations, but nothing too scary; a suggested reading list is offered for more rigorous details. Stewart does a fine job of balancing history and mathematical theory in a book as easy to enjoy as it is to understand.Line drawings. (Apr.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.