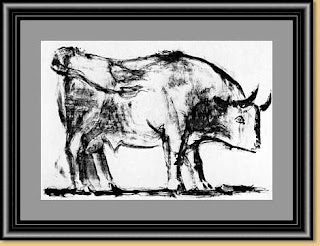

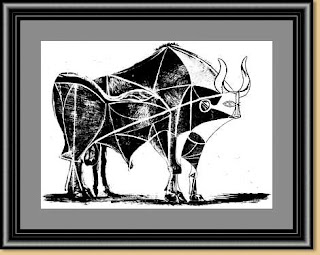

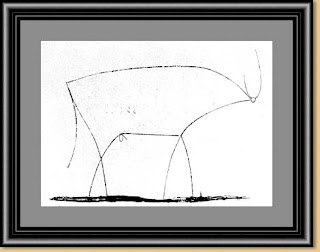

Bull ( Plate I. - December 5 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Pablo Picasso created 'Bull' around the Christmas of 1945. 'Bull' is a suite of eleven lithographs that have become a master class in how to develop an artwork from the academic to the abstract. In this series of images, all pulled from a single stone, Picasso visually dissects the image of a bull to discover its essential presence through a progressive analysis of its form. Each plate is a successive stage in an investigation to find the absolute 'spirit' of the beast.

To start the series, Picasso creates a lively and realistic brush drawing of the bull in lithographic ink. It is a fresh and spontaneous image that lays the foundations for the developments to come.

Picasso used the bull as a metaphor throughout his artwork but he refused to be pinned down as to its meaning. Depending on its context, it has been interpreted in various ways: as a representation of the Spanish people; as a comment on fascism and brutality; as a symbol of virility; or as a reflection of Picasso's self image.

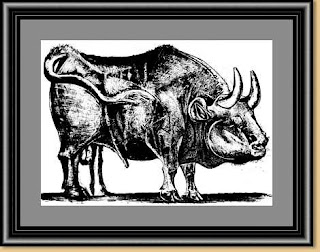

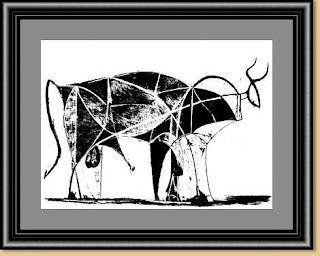

Bull ( Plate II. - December 12 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

At the second stage of the lithograph, Picasso bulks up the form of the bull to increase its expressive power and achieve a more mythical presence.

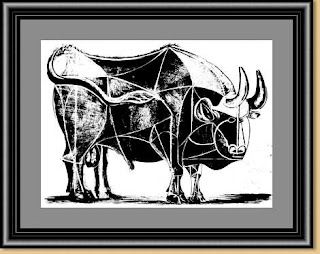

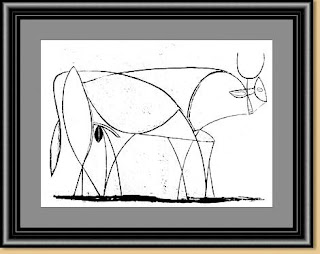

Bull ( Plate III. - December 18 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

On Plate III. the development takes a change of direction. Picasso stops building the beast and starts to dissect the creature with lines of force that follow the contours of its muscles and skeleton. He cuts into the form of the bull much in the same way as a butcher would cut up a carcass. In fact, he was known to have joked with the printers about this butcher analogy. Also at this stage, Picasso introduces the use of a lithographic crayon to add more detail to the surface texture of the animal's skin. The overall effect is reminiscent of Dürer's famous images of a rhinoceros.

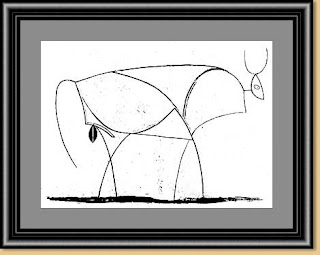

Bull ( plate IV. - December 22 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

Plate IV. sees the artist start to abstract the structure of the bull by simplifying and outlining the major planes of its anatomy.

Ten years earlier Picasso had said that "A picture used to be a sum of additions. In my case a picture is a sum of destructions." In view of this statement, lithography seems to be the most natural choice of media for this series of prints. One of the technical advantages of lithography over other printmaking techniques is that you can both add to and subtract from the image with relative ease.

Bull ( plate V. - December 24 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

The simplification and stylisation of the image continues on Plate V. Picasso starts to erase sections of the bull in order to redistribute the balance and reorganise the dynamics between the front and the rear of the creature.

First, he reduces its massive head and compresses its features into the small area that was previously the bull's forehead. By enlarging the eye and flattening its horns into a more lyrical design, he creates a sharper focal point at the front of the animal.

Next, he erases a section of the back which has the counter effect of raising the front. He literally underlines this change with the bold white line that runs diagonally across the animal, parallel to the new angle of the back. As a counterbalance to this movement, he strengthens a line that runs in the opposite direction across the middle of the body, parallel to the shoulders at the front.

Picasso's process of development is like building a house of cards where balance and counterbalance of the individual elements is crucial to the stability of the whole.

Bull ( plate VI. - December 26 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

At this stage, another new head and tail are created to conform to the style and direction of the developing image.

Picasso introduces more curves to soften the network of lines that crisscross the creature. Once again he adjusts the line of the back which now begins as wave on the shoulders and flows like a pulse of energy along the length of its body. The two counterbalancing lines discussed in the previous plate are extended down the front and back legs to act like structural supports for the weight of the bull. All three of these lines intersect at a point that suggests the bull's center of balance. Through the development of these drawings, Picasso is beginning to understand the displacement of weight and balance between the front and rear of the animal.

Bull ( plate VII. - December 28 1945 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

As Picasso recognizes the balance of form in the bull, he starts to remove and simplify some of the lines of construction that have served their function. He then encases the essential elements that remain in a taut outline.

Bull ( plate VIII. - January 2 1946 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

Plate VIII. continues the reduction and simplification of the image into line with another reconfiguration of the head, legs and tail.

Bull ( plate IX. - January 5 1946 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

While continuing to have fun with the drawing of the head, Picasso now erases the remaining areas of tone and finally reduces the bull to a line drawing. Only the creature's reproductive organ retains its shading in order to emphasise its gender.

Bull ( plate X. - January 10 1946 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

At this penultimate stage, the more complex areas of the line drawing are removed to leave only a few basic lines and shapes that characterize the fundamental forces and correlation of forms in the creature.

Bull ( plate XI. - January 17 1946 )

(eleven developments of a lithograph)

In the final print of the series, Picasso reduces the bull to a simple outline that is so carefully considered through the progressive development of each image, that it captures the absolute essence of the creature in as concise an image as possible.