-by Paul Grant (follower of Basho)

Gorky, Arshile - ärˈshīl gôrˈkē, c.1900–48, though most often considered and categorizes an American painter, is more corectllty identified, in my opinion, as a great Armenian artist.

The man referred to as Arshile Gorky was born in Armenia as Vosdanig Adoian.

Can one imagine writing about the poet and Holocaust survivor Paul Celan without noting that he survived the Nazi's extermination plan for the Jews? And that his parents were Holocaust victims? Would one write about Marc Chagall's early work without delving into the climate of anti-Semitism in Russia during the first decades of the century? Or about Picasso's paintings of the '30s without a consideration of what the Spanish Civil War meant to him? It should be equally unthinkable to write about Gorky without articulating the context and facts of the Armenian Genocide. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1248/is_n2_v84/ai_18004719/pg_2

"So there is, in Gorky's life, the suggestion of the absent father, the overachieving mother, and a child who preferred to carve or to draw, rather than to speak. And, in the distant background, a genocide."Matthew Spender, "Arshile Gorky's Early Life," in Arshile Gorky: The Breakthrough Years, pp. 28-32.

Gorky's birthplace was the lakeside village of Khorkom. A few miles to the west of Khorkom was the island of Akhtamar, with its famous tenth-century church, which Gorky later praised as "that jewel established in our crown of beauty."

In the years around 1910, Gorky's father attempted to avoid forced conscription into the army. He emigrated to America when Gorky had only 4.

As a tradition, the Ottoman Army drafted non-Muslim males only between the ages of 20 and 45 into the regular army. If Gorky's father had been conscripted - he would have faced almost certain death in 1915. "In the aftermath of the disastrous outcome of Enver Pasha’s winter offensive at Sarikamis, the Armenian soldiers in the regular army were disarmed out of fear that they would collaborate with the Russians. The order for this measure was sent out on 25 February 1915. Finally, the unarmed recruits were among the first groups to be massacred. These massacres seem to have started even before the decision was taken to deport the Armenians to the Syrian desert. (Source http://www.hist.net/kieser/aghet/Essays/EssayZurcher.html)

This massacre of Armenians was not the first. Armenians lived in bad conditions. In the Ottoman Empire, in accordance with the Muslim dhimmi system, Armenians, as Christians, were guaranteed limited freedoms (such as the right to worship), but were treated as second-class citizens. Christians and Jews were not considered equals to Muslims: testimony against Muslims by Christians and Jews was inadmissible in courts of law. They were forbidden to carry weapons or ride atop horses, their children were subject to the Devshirmeh system, their houses could not overlook those of Muslims, and their religious practices would have to defer to those of Muslims, in addition to various other legal limitations.[3] Violation of these statutes could result in punishments ranging from the levying of fines to execution.

Massacres of 1894-1896The Hamidian massacres, also referred to as the Armenian Massacres of 1894-1896, refers to the massacring of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire, with estimates of the dead ranging from 80,000 to 300,000[1], and at least 50.000 orphans as a result[2]. The massacres are named for Abdul Hamid II, whose efforts to reinforce the territorial integrity of the embattled Ottoman Empire reasserted Pan-Islamism as a state ideology.[ Akcam, Taner. A Shameful Act. 2006, page 44.

Massacres of 1909The Adana massacre occurred in Adana Province, in the Ottoman Empire, in April 1909. A religious-ethnic clash[1] in the city of Adana amidst governmental upheaval resulted in a series of anti-Armenian pogroms throughout the district. Reports estimated that the massacres in Adana Province resulted in 15,000 to 30,000 deaths.[2][3][4][5]

Turkish and Armenian revolutionary groups had worked together to secure the restoration of constitutional rule, in 1908. On 31 March (or 13 April, by the Western calendar) a military revolt directed against the Committee of Union and Progress seized Istanbul. While the revolt lasted only ten days, it precipitated a massacre of Armenians in the province of Adana that lasted over a month.

The massacres were rooted in political, economic,[6] and religious differences. The Armenian population of Adana was "richest and most prosperous", and the violence included the destruction of "tractors and other kinds of mechanized equipment."[2] The Christian-minority Armenians had also openly supported the coup against Sultan Abdul Hamid II, which had deprived the Islamic head of state of power. The awakening of Turkish nationalism, and the perception of the Armenians as a separatist, European-controlled entity, also contributed to the violence.[2]]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adana_Massacre)

The Tehcir LawThe Tehcir Law ("Regulation for the settlement of Armenians relocated to other places because of war conditions and emergency political requirements") was passed by the Ottoman Parliament on May 27, 1915 and allegedly came into force on June 1, 1915, with publication in Takvim-i Vekayi, the official gazette of the Ottoman State

With the implementation of Tehcir law, the confiscation of Armenian property and the slaughter of Armenians that ensued upon the law's enactment outraged much of the western world. While the Ottoman Empire's wartime allies offered little protest, a wealth of German and Austrian historical documents has since come to attest to the witnesses' horror at the killings and mass starvation of Armenians.[32][33][34] In the United States, The New York Times reported almost daily on the mass murder of the Armenian people, describing the process as "systematic", "authorized" and "organized by the government." Theodore Roosevelt would later characterize this as "the greatest crime of the war."[35]

The Armenians were marched out to the Syrian town of Deir ez-Zor and the surrounding desert. A good deal of evidence suggests that the Ottoman government did not provide any facilities or supplies to sustain the Armenians during their deportation, nor when they arrived.[36] By August 1915, The New York Times reported that "the roads and the Euphrates are strewn with corpses of exiles, and those who survive are doomed to certain death. It is a plan to exterminate the whole Armenian people."[37]

Ottoman troops escorting the Armenians not only allowed others to rob, kill, and rape the Armenians, but often participated in these activities themselves.[36] Deprived of their belongings and marched into the desert, hundreds of thousands of Armenians perished.

Naturally, the death rate from starvation and sickness is very high and is increased by the brutal treatment of the authorities, whose bearing toward the exiles as they are being driven back and forth over the desert is not unlike that of slave drivers. With few exceptions no shelter of any kind is provided and the people coming from a cold climate are left under the scorching desert sun without food and water. Temporary relief can only be obtained by the few able to pay officials.[36]

Arshile Gorky's mother, Lady Shushanik der Marderosian, belonged to a distinguished Armenian family that could trace its origins back to the fifth century A.D. She was born in 1880 in Vosdan, a town just to the south of Lake Van in what is now eastern Turkey, in a valley of rushing streams and poplar groves. Just to the east of Vosdan stood the ancestral monastery (or vank) of the der Marderosians. At the time of Gorky's birth, in 1904, nearly 40 of his maternal ancestors lay buried at the vank, under elaborately carved tombstones. In later life he referred to his mother as "the last breath of Van nobility." She was his first teacher, and she seems to have been determined that her son should become an artist. (http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G1-17501985.html)

Front View of St. Cross Monastery of Varak in Van.

When the family moved to the city of Van, in 1910, Lady Shushanik made sure that her son became familiar with the collection of illuminated manuscripts housed in the great monastery of Varak, which lay nearby. In a letter of 1945, Gorky wrote rapturously of "the medieval Armenian manuscript paintings with their beautiful Armenian faces, subtle colors, their tender lines and calligraphy." He might almost be describing his own paintings and drawings.

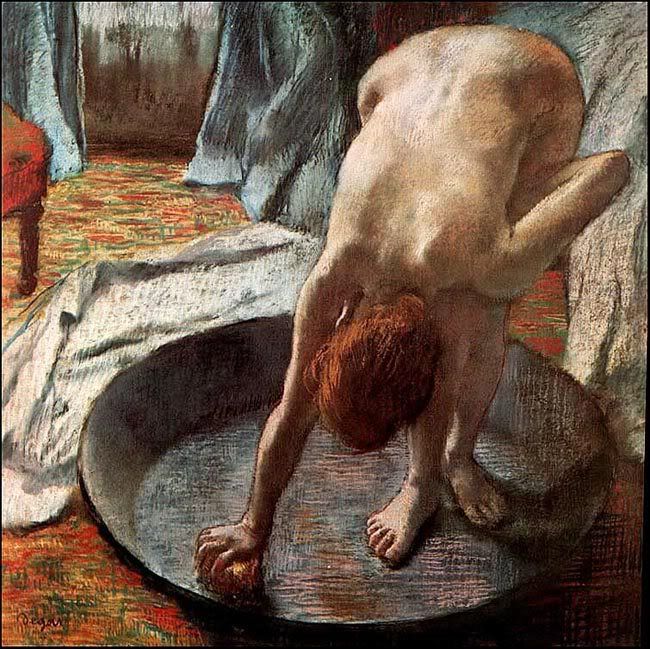

1938 Khorkom (above), and related works on the same theme, stand at this crossroads in the fertile years when Gorky felt his art should ocnvery his ‘living dreams’ of childhood memories and his ancient homeland Traces of Cubist still life can be glimpsed in Gorky’s paintings of the 1930s, including the present work, Khorkom, where certain forms, such as a slice of apple, a palette, and the profile of a bird are vaguely identifiable amid the composition.

1938 Khorkom (above), and related works on the same theme, stand at this crossroads in the fertile years when Gorky felt his art should ocnvery his ‘living dreams’ of childhood memories and his ancient homeland Traces of Cubist still life can be glimpsed in Gorky’s paintings of the 1930s, including the present work, Khorkom, where certain forms, such as a slice of apple, a palette, and the profile of a bird are vaguely identifiable amid the composition.In 1915, when the Ottoman government embarked on its final solution of the "Armenian question." In April of that year, Khorkom was burnt to the ground, and the six members of Gorky's family who had remained in the village were murdered. In Vosdan seven cousins were killed, and the der Marderosian monastery was razed to the ground. The manuscripts of Varak were burnt, and Van was subjected to a savage month-long bombardment that reduced it to rubble. Gorky and his family then walked 150 miles to Yerevan, in Russian Armenia. There, four years later, his mother died in his arms. She was not yet 40. Gorky described her as "the most esthetically appreciative, the most poetically incisive master I have encountered in all my life."

In 1920, Gorky and his sister arrived at Ellis Island, and eventually moved to Providence, Rhode Island, where his father had emigrated earlier.Gorky was reunited with his father when he arrived in America in 1920, aged 16, but they never grew close. In 1922 Gorky enrolled in the New School of Design in Boston, eventually becoming a part-time instructor. During the early 1920s he was influenced by impressionism, although later in the decade he produced works that were more postimpressionist. Gorky moved to New York around 1925, and changed his name, passing himself off as Maxim Gorky's nephew- Arshile (a variant of Achilles) Gorky (an allusion to Maxim Gorky), and by repeatedly claiming to have been born in Tiflis, a city he merely passed through on his way to America. During this time he was living in New York and was influenced by Paul Cezanne. In 1927, Gorky met Ethel Kremer Schwabacher and developed a life lasting friendship. Schwabacher was his first biographer.

Arshile Gorky -"Organizations" painted between 1933-1936

Arshile Gorky -"Organizations" painted between 1933-1936Gorky talked of being "with" painters: "I was with Cézanne for a long time and then naturally I was with Picasso."[2] In the 1940s he was affected by the work of the European Surrealists, particularly Roberto Matta Echaurren. He married Agnes Magruder in 1941, and called her “Mougouch,” an Armenian term of endearment. In the summer of 1942 on a visit to Connecticut he began to work from nature, something he had not done for almost fifteen years. He was inspired by Kandinsky's early abstract landscapes as well as Miró 's and Picasso’s fusing of personal memories into his own procreant works from nature. The next year was spent at Crooked Run Farm, Mougouch’s parents’ estate in Virginia, where Gorky began a series of drawings in which the forms of nature were transformed into the artist’s singular abstract style. There he produced hundreds of drawings which he later drew on for his paintings. Landscape and interior space seemed to mingle and he emerged as a truly original and important artist.

In 1946 Gorky endured a devastating studio fire where he lost much of his work, then a colostomy for rectal cancer, and in 1948 a car accident left his neck fractured and his painting arm paralyzed (

Julien Levy

Julien Levy, the famous art dealer was driving but only Gorky was injured).

His jealousy, aggression and paranoia were made worse by his tragedies, and the marriage collapsed under the strain. Mougouch, worn down by his dominance, hostility and violence, and out of desperation rather than betrayal, had a brief affair with Matta . However, Gorky felt betrayed; in a collar brace and brandishing a cane with his only functional hand, threatened Matta: “I’m going to give you a good beating. You are very charming, but you have interfered with my family life.” Matta fled, Gorky returned to his studio and hanged himself. (3)

Andre Breton

Andre BretonThe tragic death of the man Breton considered one of the greatest painters in America devastated him, and it incensed him to think that his protégé, Matta, had precipitated the suicide of the man he cherished.

Roberto Matta [Chilean-born French Surrealist/Abstract Expressionist Painter, ca.1912-2002]

Roberto Matta [Chilean-born French Surrealist/Abstract Expressionist Painter, ca.1912-2002]When Matta tried to explain that he had merely followed surrealist precepts, allowing him to be guided by unconscious desires (paraphrasing Marx, Breton had proclaimed “to each according to his desires”), the usually courteous and courtly Breton, like a modern Jeremiah, shrieked, “Assassin! Murderer!” He summoned a meeting of the Surrealist circle and Matta was excommunicated from the Surrealist group for “intellectual disqualification and moral ignominy.” (3)

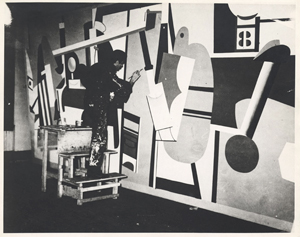

arshile gorky working on Aviation

arshile gorky working on AviationGorky hanged himself in Sherman, Connecticut, in 1948, at the age of 44. He is buried in North Cemetery in Sherman, Connecticut.

"Singing Tumanian's poems is a required part of my conduct when painting." (Mooradian, Arshille Gorky Adoian, pp. 287, 284. Hovaness Tumanian (1869-1923) was a major Armenian poet of the period.)

But still you live, standing erect in spite of all your wounds

on the mysterious journey of time, past and present,

still standing, wise and pensive, and sad, with your God ...

And the dawn of life´s happiness will come,

its light at last in thousands upon thousands of souls;

and on the sacred slopes of your Mount Ararat

will shine forth at last the flame of the time to come.

Then, with the dawn, new songs and new poems

will be on the lips of the poets.Other Sources:

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G1-17501985.html

www.thecityreview.com/f00scon1.htm

(3)http://www.oberlin.edu/amam/Gorky_Plough.htm

http://www.martinries.com/article2007AG.htm

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1248/is_n2_v84/ai_18004719/pg_1

5.0 out of 5 stars Life changing book, February 28, 2001

By A Customer

I read this book during a recent illness and I am glad of it because I was able to concentrate fully and stay within the world which the author so skilfully evokes. I have rarely found a biography of an artist, especially a modern one, so lovingly and painstakingly portrayed with brushstrokes just like a painter to produce image after image and make the man come alive in such an engaging way. I learned about the history of the ARMENIANS but through his eyes and yet the scholarship and objectivity shone through. So many insights and beautiful stories, such a strong sense of place, whether in long-lost Armenia or Boston of the 20s or New YOrk of the 30s and 4os , the characters who weave through this incredible tapestry, no a carpet. This writer belongs to the tradition of Armenian troubadours who were storytellers and sang their songs in verse in many languages. I felt the narrative had a poetic lilt and yet she kept back her obvious involvement in the subject. In her introduction which is worthy of attention Nouritza Matossian tells of her own family and their wanderings because of the Genocide, her desire to keep an even balance and not to succumb to the despair of her foretfathers. This book is a vindication of a culture which has been hammered and a Genocide which needs to be acknowledged. It tells of the courage of exiles and immigrants who brought such skills and moral values to this country which did not accept them very often. The accounts of Gorky's pursuit of excellence in art, his love for his mother and her inspiration are universal themes. I saw him as a quixotic, temperamental and charming character whom I would have loved to know. She brought him alive and I cared for him so much that I could hardly bear to finish the book, knowing that he would die. I received a great gift in understanding how it is possible for someone who has lived at traumatic life to transcend his suffering and 'give something to the world' as he said to Leger, something good. His paintings are incredibly beautiful and I see l know that he paid an even greater price than the loss of his childhood for those canvases, he paid for them with his health and security. Gorky's suicide has always puzzled me and I understand it for the first time after reading Matossian's book twice. The discussion of art and ideas, her ability to interpret him and even to depict the work is accurate and vivid. I saw from her website www.arshile-gorky.com that she performs a one-woman show in which she tells his story with slides and music as his mother, sister, sweetheart and wife. Those four characters are in the book and she pays tribute to them. It must be wonderful to hear this author tell her extraordinary story in her own words because this is a book which rings with her love and commitment for her subject and that is a rare and generous gift. All I could wish is that this book were even longer because I hated putting it down at the end. It changed my attitude to many things in my own life. This book deserves to win prizes.

From Publishers Weekly

Purely out of artistic ambition, Armenian-American abstract painter Gorky (1895-1948; born in Turkey as Vostanig Adoian) fabricated a new identity, complete with an Ivy League education and personal histories with master artists, on arriving in the United States. Spender (Within Tuscany), who is married to Gorky's oldst daughter, unhesitatingly exposes the painter's many "tall tales." He also assesses Gorky's difficulty in arriving at his own aesthetic until late in life in terms of both the artist's ties to the artistic patriarchs of the previous generation, the Surrealists (including Breton, Duchamp and Brancusi) and his complex status as a forerunner who eventually became alienated from the New York Abstract Expressionists (particularly de Kooning and Rothko). Spender derives much information from anecdotal sources, including an interview with de Kooning, and assumes a chatty tone in dealing with other artists. But he becomes increasingly less sympathetic to Gorky, whose last years are presented from the perspectives of Spender's wife and her mother. Nonetheless, painting constantly despite failing health, family problems and critical indifference, Gorky's frustrations are heartbreaking. Equally compelling is the window opened on New York's art scene when it was still a small clique. Gorky was so in love with the "artist" archetype that he not only lied about himself but also plagiarized anecdotes, artistic statements, love letters and possibly even his own suicide note. Spender preserves the personal dimensions of his subject while demonstrating that the painter should have adopted a youthful declarationA"I shall be a great artist or if not a great crook"Aas his motto. 90 b&w illustrations.

Copyright 1999 Reed Business Information, Inc.